For nearly a decade, state Assemblymember Michael Benedetto has embarked on a legislative effort to eliminate tackling in youth football for ages 12 and under, and shift toward non-contact flag football. Responses to the bill over that time — and the possibility of scaling back full-contact and tackling in youth football — have set off intense and sometimes visceral reactions. Benedetto told the Bronx Times he’s been accused of attempting to “wussify” the game of football, a sport that has long-revered playing through pain.

“Football is so ingrained in our culture that I’ve heard concerns about this bill that it’s un-American, and that I’m trying to get rid of football entirely,” said Benedetto. “This bill is to protect our young kids from possibly having long-term brain damage that will affect them for rest of their lives.”

The reasoning behind Benedetto’s bill is supported by the ever-expanding science on head trauma as a 2021 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study reported that youth tackle football athletes ages 6-14 sustained 15 times more head impacts than flag football athletes during a practice or game and sustained 23 times more high-magnitude head impacts.

And the bill — which has never made it out of committee after years of pushback from lawmakers on both sides of aisle — isn’t without precedent.

In 2019, America’s northern neighbor Canada banned tackle football for kids 12 and under because of player safety concerns after participation dwindled by roughly 40% over the course of the past decade amid rising awareness of the impact of head trauma on brain health.

The U.S. is also starting to see a similar decline in youth participation rates in America’s most popular sport.

Data from the Aspen Institute’s State of Play report shows that from 2020-2021, participation in tackle football for kids ages 6-12 declined nearly 18%. Since 2016, the institute says, tackle football participation rates for this age group have decreased 29% while flag football rates have gone up 15%, with those flag footballers outpacing the number of tackle football participants by more than 300,000 in 2021.

“Youth football participation is declining, and rather seeing a sport that many people love phase out, I’d like to find ways where kids can play this game safely,” said Benedetto, whose bill finally has a co-sponsor this year in state Sen. Luis Sepulveda.

But the bill’s lack of traction, Benedetto said, could be chalked up to a myriad factors including America’s reverence for football, and the desire for those on the sidelines and on the field, to preserve “the spirit of the game.”

A risk worth taking

Current estimates cite that 3 million children between the ages of 6 and 14 play organized tackle football. And while youth football has high numbers of participants, it also has the highest injury rate in sports, according to various medical studies including Stanford Children’s Health Hospital.

It is estimated that more than 80% of children will sustain an injury at some point playing tackle football. But for some, that’s the price you pay for the sport you love.

Jose Dominguez, 9, a Bronx-born gridiron warrior who plays travel football, couldn’t imagine not tackling in his games. He’s slightly undersized for a typical middle linebacker, but he plays with tremendous heart and hustle that he hopes one day earns him a full-ride to a Division I program.

Dominguez told the Bronx Times that he’s suffered two concussions in the past two years after colliding head-to-head with ballcarriers. For Dominguez, the dizzy spells, the headaches and newfound sensitivity to light is worth the price of playing a game he loves, and that hopes takes him to new places.

“How would I get better? If I never tackled (as a linebacker), I would get smoked in the next level.” he said. “There’s this adrenaline I get from tackling. I think my coaches teach me properly and if you can’t (tackle) properly, you shouldn’t be playing. But they shouldn’t try taking tackle football away from us.”

Rippy Phillips, a football lifer with nearly 40 years playing, coaching and advocating for the game, believes that Benedetto’s bill is “thoughtless” and doesn’t reflect the current measures professional football and amateur levels have taken to address player safety concerns.

“The game of football has made strides from youth to college in 35-40 years, and I don’t think football gets enough credit for how it’s adapted to our general awareness of concussions and head injuries,” said Phillips. “But the bill is 10 to 15 years too late. This is not the same game it used to be. To me, it’s safer.”

Pop Warner Football — with more than 225,000 football players from 5-14 years old — implemented strict guidelines in place to minimize injury, becoming the first youth organization in 2009 to limit contact during practices; capping it at only 25% of practice time. They also eliminated kickoffs for the youngest players and require a doctor’s permission for a child who has suffered a “suspected head injury” to return to play.

While Pop Warner Football offers flag football teams, tackle football starts at age 5.

A representative of Pop Warner told the Bronx Times that using their player safety guidelines and their “Heads-Up Football Training” results in 87% fewer injuries.

Coaches, more than any other cog in the football infrastructure, have become vital to player safety. For the Bronx Outlaws, a youth tackle football program based outside St. Mary’s Park in the Mott Haven section, they employ a three-month offseason to prepare players for contact, and hammer the fundamentals of the game before the season starts around Labor Day weekend.

Victor Green, director and head coach of the Bronx Outlaws, says his program has adopted USA Football player safety protocols which include 60-plus lessons of video and instructional material to help coaches refine their teaching methods to help their players learn the core fundamentals and building blocks of blocking, defeating blocks and tackling.

For Green, the issue of player safety in youth football depends on the qualifications and intentions of coaches and programs to prioritize player safety protocols over winning and losing.

“We take player safety seriously because we want to protect our players, and give our parents a reason to trust us with your kids, and give them the tools to play this game safely,” said Green. “I’ve seen a lot of youth football programs do this the wrong way, and we’re going to do this in a way that keeps our players safe and our parents eager to bring them back.”

While Phillips may not recognize the game he grew up playing — way less time to practice tackling drills and limits on contact — he knows his instruction is the difference between a good play and an unfortunate injury.

Proper tackling techniques, youth football coaches say, stress players to make impact with their shoulder and arm while keeping their face masks up and eyes to the sky in an effort to keep their heads out of the play. In fact, some coaches like Phillips would rather his players miss the tackle than hurt themselves going headfirst.

But concussion specialists and head trauma experts aren’t just concerned about the highlight reel hits.

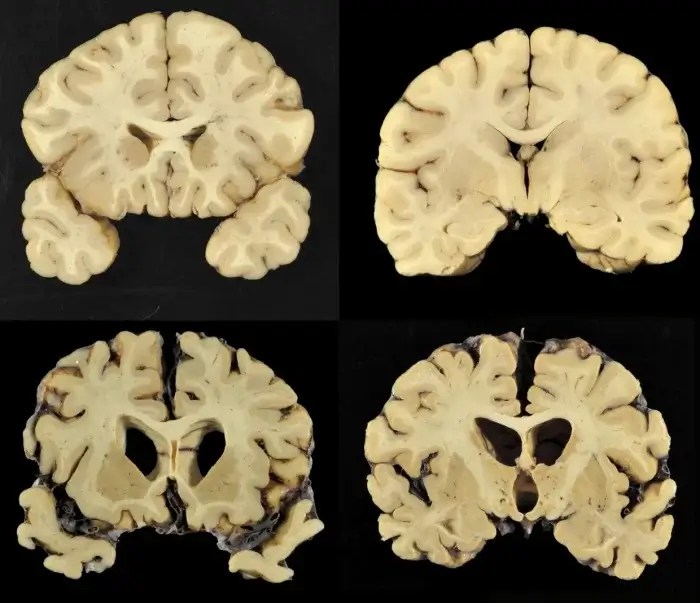

There’s also a growing concern that lower magnitude, more frequent subconcussive impacts — bumps and blows to the head that do not result in a concussion — could be the real ticking time bomb that leads to serious long-term repercussions, including the neurogenerative disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

New data from Boston University suggests that CTE risk might be much higher than previously thought. Of the 376 former NFL players who participated in their study, a whopping 345 have been diagnosed with CTE — more than 90%. A degenerative brain disease found in athletes, military veterans and others with a history of repetitive brain trauma, CTE causes depression, suicidal thoughts, aggression and mood swings, and can only be diagnosed post-mortem.

This past season, the NFL continued to struggle with perceptions of player safety. Miami Dolphins QB Tua Tagovailoa suffered at least two concussions during the 2022-23 campaign, and the team’s medical staff came under heavy criticism for their response to his head injuries.

And during a nationally-televised primetime matchup on Jan. 2 between the Buffalo Bills and Cincinnati Bengals, the world watched uncomfortably as Bills safety Damar Hamlin suffered cardiac arrest on the field after making a tackle, leading to a lighting rod of morning-show debates on player safety.

NYU Langone sports medicine specialist Dr. Dennis Cardone doesn’t recommend tackle football for kids 12 and under due to the risks associated with a developing brain. Despite the progress youth football has made to ensure player safety, Cardone feels it has lagged behind other youth contact sports such as hockey, which is all but phased out full contact.

“Football has done some things no doubt to prevent the prevalence of head injuries in the sport. … These things have taken affect at the professional level but most importantly at the high school and collegiate levels,” said Cardone. “But youth football is still lagging a bit behind other youth contact sports such as hockey, lacrosse, and I think that should give parents something to consider when finding a sport for their child.”